Throwback Thursdays – Ted Lindsay

Robert Blake Theodore “Ted” Lindsay left the hockey world – and the world in general – a bit short-handed on Monday. After passing away at the age of 93, he’s been remembered across many platforms, in many ways, by many people over the last few days.

He had skill. He had (tons and tons of) grit. He was a gentleman. He was a legend.

And yes, those are all parts of what make Lindsay who he was.

It still feels weird to say “was” instead of “is”.

One of the privileges of having a genuine interest in the history of hockey and the people that made it what it is, as well running this weekly Throwback Thursdays segment, is that you feel connected to the past. Lindsay constantly comes up while researching articles, and his history was one of the inspirations for my current series – a series on NHL Trophies and the people behind the trophy names. It’s the reason I chose his award to kick off the series with the first article. I’ve actually taken a break from that series for this week just to write this article.

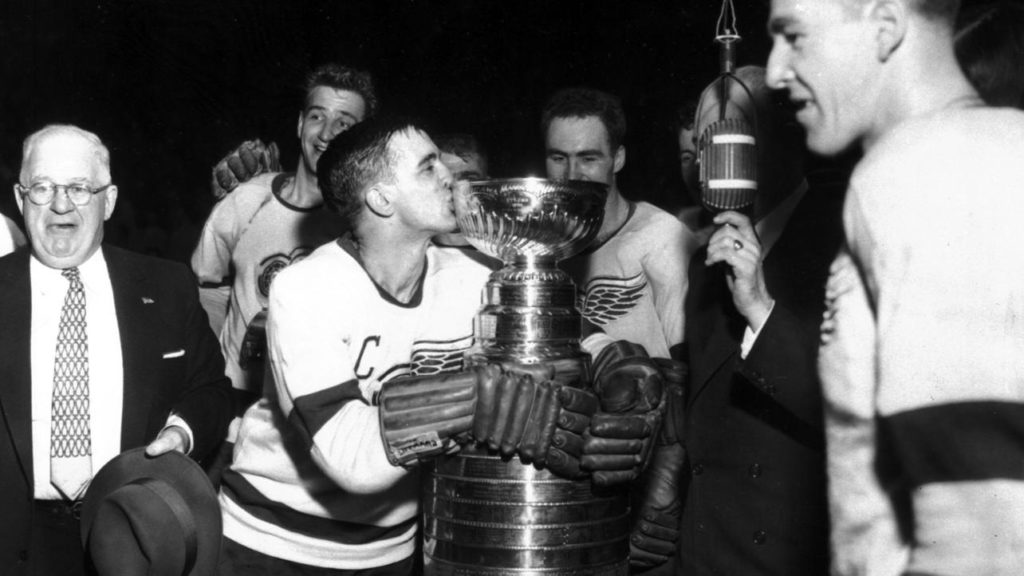

Lindsay left his mark all over the hockey history books. He won the Memorial Cup with the Oshawa Generals in 1944, was an eight time first team all-star, he was a Stanley Cup champion, he led the league in scoring one season, he formed one of the most famous lines in league history with Gordie Howe and Sid Abel (the Production Line), he was a Hockey Hall-of-Famer, his number is retired in Detroit, and many more accomplishments I could go on about on the ice.

Geez, he was even the first player to lift the Cup over his head on the ice after winning it in a salute to the fans, a tradition carried on to this day.

All of that being said, I felt it was imperative to write about his most lasting effect on hockey and about his biggest overall effect and change on the game. An off the ice change to the business side of hockey that still resonates throughout the NHL today, and will forever more.

That change? The creation of the first NHL Players Union.

To get a little bit of insight of why Lindsay and others were interested in creating a union, all we need to do is look into Lindsay’s own words from an old article by Kevin Shea on the Hockey Hall of Fame’s website:

“We never had agents back at that time. It was a dictatorship during the six-team league. That’s what it was. They’d say, ‘Jump,’ and you’d say, ‘How high and how many times?’ You just reacted that way. You would agree to a contract but you couldn’t even take that contract out of the manager’s office. They would say, ‘It’s against the by-laws.’ Every player in that six-team league, all he wanted to do was play hockey. That was our livelihood – we never argued the point. They gave us our contracts. They said, ‘Take it, that’s all you’re going to get.’ So I just wanted to get a voice as a team.”

It’s a great concept, but how do you go from thoughts of getting players together to forming a union?

Lindsay’s first step was a call placed to Bob Feller, at the time he was head of the American League Baseball Players’ Association. Feller gave Lindsay some advice but told him that legally, they were in for an uphill battle.

“After talking with Bob (Feller), he put me in touch with lawyers in New York. The laws were way different back then. If the laws we have today would have been in place back then, all the owners and managers would have been in jail. It was like slavery back then.”

Lindsay would go on to recruit players during various games, including the 1956 NHL All-Star game. Some of the first enlistees including the likes of Montreal’s Doug Harvey, Toronto’s captain Jim Thompson, Chicago’s Gus Mortson, Ranger and Red Wing Hall of Famer Bill Gadsby, and Bruins’ Fernie Flaman.

As Lindsay recalled in the HHOF article, players agreed with him but commitment was difficult due to the cost involved.

“The All-Star Game was going to be in Detroit because we won the Stanley Cup. Doug Harvey (of the Montreal Canadiens) was one of the more intelligent guys in the National Hockey League. Doug was a strong force. I don’t know how it worked out but I got to Doug and told him what I had in mind and with the top players all coming into Detroit, we wanted to be able to sit down quietly – this was not to be publicized; nobody was to know we were doing this. We did it and it worked out. You had to put $100 in because we had to pay the lawyers. To get $100 out of the players back in those days was tough. We were only making $5,500 to $7500 (per year) and guys in the minor leagues were making $3500 to $4000.”

The union or Player’ Association (as the players thought union was too strong of a word) was unveiled on February 11, 1957. Lindsay recalled the initial reaction.

“All the guys went back to their rinks and I went back to Detroit the next day. I knew darn well when I got to the Olympia (the home arena of the Red Wings at that time), they weren’t getting dressed for practice because there was going to be a war in there. Sure enough, Adams was steaming around in the dressing room. It looked like somebody painted him with a red paint brush because his blood pressure was so up so much. He started to condemn it all.”

The fallout was seen right way. Conn Smythe labelled Leafs’ Thompson as a “traitor”. He was even benched during parts of the season despite his captaincy before being traded to Chicago. Many other players were traded or sent to the minors due to their involvement including Harvey, who was considered the best defenceman of the time, but was moved to the New York Rangers to get rid of the dressing room issues brought on by his union involvement.

Lindsay saw the worst of it. He was first stripped of his captaincy of the Red Wings, and was then traded to the Chicago Black Hawks along with fellow Hall of Famer Glenn Hall to put him off his pursuit of an association. Once Lindsay was in Chicago, Red Wings GM Jack Adams continued his assault on Lindsay, including an attempt to leak an inflated contract to the press, which dissuaded multiple teams and players from joining his new association.

Lindsay had seen enough, started an anti-trust lawsuit, claiming the league had held monopoly since 1926. In 1958, the the lawsuit was decided out of court, with the league bending to many of Lindsay’s demands. That being said, Adams and other General Managers has soured the players opinion of the association to the point it was disbanded the same year. The official NHL Players’ Association would not be formed until 1967.

At the time, Lindsay felt that had he waited to try and certify the union in Chicago instead of Detroit, it would have had a better chance to succeed.

“We picked Toronto as the place to certify in Canada. We picked Detroit in the U.S. I was in Chicago at the time. If I had known that Detroit was going to turn out like that, I would have done it in Chicago. The situation in Detroit was what hung us.”

Lindsay may have failed to unionize the players on the first attempt, but the fact he was able to generate a settlement from the league was the first step towards the current NHLPA. The association clearly sees the paramount role Lindsay played in the development of the union. It recognized the importance of Lindsay in the founding of the association by releasing the following as one of the opening lines in a press release after learning of his passing:

“All NHLPA members, current and former, owe a great deal of gratitude to Ted.”

We, as hockey fans, owe him a great deal as well. We may never have another Ted Lindsay, but we can learn lessons from how he approached the game, and life in general, to better ourselves.

Have fun playing shinny with those who have joined the rink in the clouds before you.