Throwback Thursdays – NHA demise/NHL birth

It’s Thursday, and in true #TBT style we are going way back (again) to the early days of professional hockey and the NHL. After looking at Art Ross, both as a player and an executive, this week we go to Toronto’s history. More specifically how they almost became the Philadelphia Leafs instead of the Toronto Maple Leafs. This story will require three parts, the death of the NHA/birth of the NHL, the transition years of the Arenas and St. Pats, and Conn Smythe’s horse racing gamble that led to the stabilization of the franchise we know today.

The story really starts with the demise of the Toronto Blueshirts and National Hockey Association (NHA). For that we need to dive into the story of the Toronto Professional hockey Club and the NHA’s most-hated man, Eddie Livingstone, a man that caused the creation of the NHL completely out of hatred for his person.

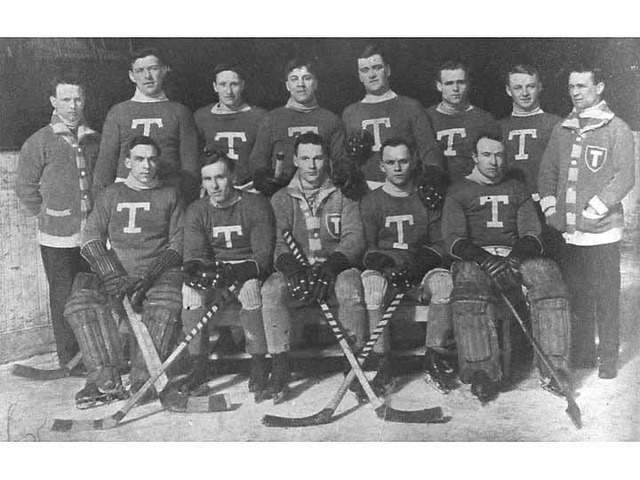

The Blueshirts were created in 1911 when Percy Quinn and Frank Robinson (as well as some small investors) purchased a franchise to be known as the Toronto Professional Hockey Club to play in the NHA for the large fee of $2,000. The Blueshirts, as they came to be known, were one of two Toronto franchises set to play in the NHA in 1911-12 at the newly minted Arena Gardens. Unfortunately the Gardens – one of the first arena’s with artificial ice – was not built in time for the 1911 season and both Toronto teams were postponed a season.

Finally, in December of 1912, the Torontos (as they were originally known), played their first game. For their inaugural season they iced an an incredible line-up that featured future Hall-of-Famers Hap Holmes, Harry Cameron, Frank Foyston, and Frank Nighbor. The all-star cast could only manage a third place finish.

Fast forward two years and Toronto were Stanley Cup champions, fittingly starting a century old rivalry by beating the Montreal Canadiens for the NHA and Cup title.

Unfortunately, Toronto’s success was short-lived. Two years of mediocrity and the beginning of the First World War led to Robinson’s decision to join the Canadian military and put the Toronto Hockey Club up for sale. With multiple bids on the team, Robinson settled on the highest bid – a bid from Edward J. Livingstone.

Livingstone’s purchase of the THC coincided with a feud the NHA had started by attempting to pry Cyclone Taylor from the Pacific Coast Hockey Association (PCHA). The PCHA responded by raiding NHA teams, including taking Toronto’s two leading scorers and their Hall of Fame goalie, Hap Holmes. Livingstone jumped on this opportunity to sell his other team, the Toronto Shamrocks -after taking the best players to fill out his Blueshirts squad of course. This meant the PCHA kept their man and raided the NHA, all while Livingstone got to start his franchise with players from his other squad to replace the departed stars. It was even suggested in 2002’s “Deception and Doublecross: How the NHL Conquered Hockey,” that Livingstone may have had a deal in place with Frank and Lester Patrick of the PCHA.

This possible deal, coupled with his abrasive personality, immediately got Livingstone off with the wrong foot with fellow owners, as former Canadian Prime Minister and hockey historian, Stephen Harper, would later explain:

“A combative, sanctimonious and generally difficult personality… [He] expected others to live rigidly by the rules while he would skirt their spirit. He regularly denounced those with whom he clashed, while demanding apologies for the thinnest of slights.”

Livingstone’s team would finish last that season and he would start another feud the following season when the NHA decided to create more fans amongst military personnel by adding the 228th Battalion as a second Toronto-based team. Livingstone was livid that another team was allowed to play out of his Toronto territory, and no one was more satisfied when the battalion had to withdraw from the league after 10 games after being called into action in WWI. However this same withdrawal created the the imbalance of uneven teams in the league that allowed for speculation of the future of the NHA.

The Canadian Encyclopedia explains what happened next best:

“The league held a meeting three days later. Livingstone declined to attend, due to illness; instead, he sent a private telegram to league president Frank Robinson indicating that he supported a five-team circuit for the rest of the season. The other owners, whose teams, like Livingstone’s, had been decimated by the First World War, wanted to divide the Blueshirts among themselves to replenish their own teams’ lineups and run with just four teams. And so it went: Toronto was suspended for the rest of the season, and Livingstone was not compensated for the cancelled Blueshirts games or for the players he was compelled to loan out.”

This led to a series of lawsuits by Livingstone, and after only two seasons as an owner in the NHA, other franchisees had decided they had enough. After a meeting at the Windsor Hotel in Montreal, the owners of the Montreal Canadiens, Montreal Wanderers, Quebec Bulldogs, and Ottawa Senators decided to create a new league as they could not legally remove Livingstone from the NHA. Thus, on November 26, 1917 the National Hockey League was born – with former NHA treasurer Frank Calder being the first NHL President.

The writers of Deceptions and Double-cross sat down with former Canadiens owner George Kennedy and asked him what happened on that day, Kennedy was asked in said book of the meeting that created the NHL and if Livingstone was invited:

“No, we haven’t [invited him]. I guess we forgot. Anyway, he is still a member of the National Association, and has a franchise in that fine body. Of course he may have a little difficulty getting a place to play, and any teams to play against. Because the rest of us just resigned from the Association and formed this new league. Eddie still has his team and the Association franchise. Good luck to him. Now what about a drink?”

That same pub must have been a popular place at the time, as Wanderers owner Sam Lichtenhein (who once threatened to buy out Livingstone’s franchise and almost came to blows with him) was there to add to the matter:

“It’s strictly legal. We didn’t throw Eddie Livingstone out. Perish the thought. That would have been illegal and unfair. Also, it wouldn’t have been sporting. We just resigned, and wished him a fine future with his National Association franchise.”

Not done the sarcastic attacks on Liviingstone, Tommy Gorman (a Senators representative) added:

“Great day for hockey. Livingstone was always arguing. No place for arguing in hockey. Let’s make money instead.”

So with the Toronto Hockey Club and the NHA quickly falling apart, but not wanting to lose the Toronto market, the Quebec franchise decided to forego a year of play and let a new Toronto franchise be the fourth NHL team to round out the numbers. That franchise was awarded to the Toronto Arena Company, the owner of the Arena Gardens.

With no avenues left to pursue, Livingstone agreed to lease his players to the Toronto Arenas for the 1917-18 season. An agreement that would eventually become permanent. This was also the first step towards the Arenas becoming the St. Patricks, and going up for sale to a potential move to Philadelphia.

Stay tuned for next couple of week’s TBT, for the interesting forming years of the Leafs’s franchise, and the horse race that decided the Leafs’s entire future.