Throwback Thursday – The Original Marty McSorley

As the Finals rage on, I wanted to delve into a story that involved the Bruins and Blues for this week’s Throwback Thursday. What I found was the story of one of the most vicious attacks in NHL history. However, before I can tell you that story, to set the mood try and remember a nearly identical attack that luckily didn’t carry the same near-fatal consequences.

If you’re a hockey fan and having been living under a rock for the last couple of decades, you know what happened on February 21, 2000. You might not remember that date, or the teams (Vancouver Canucks and Boston Bruins), or what the final score was (5-2 Canucks), or that Marty McSorley and Donald Brashear had fought at 2:09 mark of the first period. What you do probably remember, however, is this:

The aftermath was swift. McSorley was indefinitely suspended, a suspension that was later increased to a full calendar year – effectively ending McSorely’s career at 17 seasons. McSorely would also be charged through a British Columbia primal court for assault, however his sentencing was such that he wasn’t really punished. All he needed to do was not play a competitive game against a team that had Brashear on it for two years and his record would be scrubbed clean of the assault.

Brashear would come back later in the season and go on to play many more seasons in the NHL with Vancouver, Philadelphia, and Washington, the LNAH in Quebec, and in the SHL with MODO in Sweden.

The point of the article is to shine a light on the original McSorley-like incident. For that, we have to travel all the way back to the summer of ’69.

It was September 21, 1969 (summer doesn’t end until September 23, so my joke still works!) and there was preseason hockey in the air – the least interesting part of the hockey season. Well, except for that one time the Philadelphia Flyers mocked the Tampa Bay Lightning’s 1-3-1 system and did nothing for a couple of minutes.

Anyways, at the time one of the most fearsome players in the NHL was a Bruins defenceman by the name of “Terrible” Ted Green. He was entering his 10th season in the NHL and had earned his reputation for his fierce competitiveness. He was a championship magnet, winning the Memorial Cup as a junior player, two Stanley Cups as a player, five more as an assistant/co-coach of the Edmonton Oilers dynasty, and three AVRO Cups as part of the World Hockey Association (WHA). He was eventually inducted in the Manitoba Sports Hall of Fame, the Manitoba Hockey Hall of Fame, and was an inaugural member of the WHA Hall of Fame.

Wayne Maki, on the other hand, was a journeyman player who was known mostly for a couple of things that weren’t positive bits of news. After playing shuttling between the minors and NHL throughout his career, he eventually found a home after he was selected in the 1970 expansion draft by the Canucks. He would lead the Canucks in scoring their first two seasons before retiring halfway through his third season in Vancouver after being diagnosed with a brain tumour. He passed away on May 12, 1974. The Canucks would retire his #11 after his death.

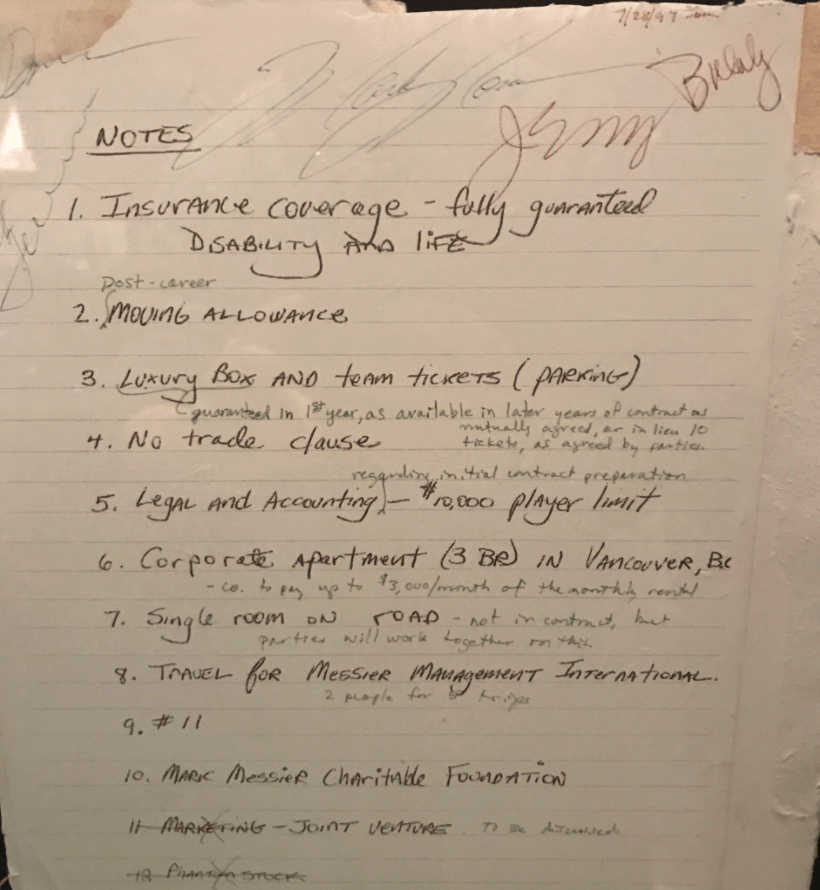

The first of the two thing’s Maki is known for is Mark Messier’s horrid tenure in Vancouver, a tenure in which he insisted in his contract that he be given #11. This despite the fact Maki’s family protested as they thought it was a disgrace to un-retire the number after Maki’s death.

The other reason Maki is remembered is that night in September of 1969.

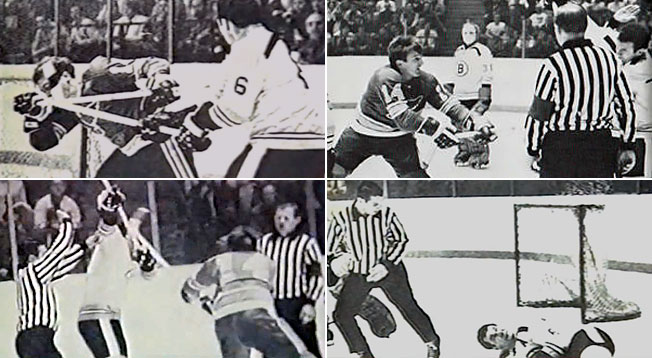

As preseason games go, it was a calm affair up until the end of the first period. Near the end of the frame Maki (then playing for the St. Louis Blues) charged Green behind the Bruin’s net.

Green recalled what happened next in his own words in the 20th Century Hockey Chronicle:

“I then reached out with my glove hand and shoved Maki in the face.”

Maki fell to the ice and recovered while spearing Green in the gut. Green smacked him with his stick below his shoulder and started to skate away. It was the last thing he remembers for the next few minutes of that night.

“My last thought was ‘I guess that’ll straighten him out.'”

Maki wanted to get the last laugh however and brought his stick down hard on Green’s head. Green went down hard and fast. He was lying on his side, convulsing. Green was nearly killed on the play. He wasn’t aware at the time, but he had suffered a compound skull fracture which eventually required a two and a half hour surgery, another brain surgery, and a metal plate being put in his head.

Ed Westfall, a Bruins teammate remembers “There was even a rumour that he had died.”

Westfall went to the hospital to check on Green on the recovery room after his surgery. Green was semi-conscious on his hospital bed, moaning while two nurses looked after him. Westfall remembers the feeling of relief when Green responded to his voice.

“I took his hand and said ‘Greenie, it’s 18.’ Instead of calling me Ed the guys called me by my uniform number. Teddy didn’t move, and I said, ‘It’s 18. Can you hear me? If you can, squeeze my hand.’ He squeezed my hand, and I felt like a new father who just got the word that the mother and infant are doing fine.”

Green did eventually fully recover and continue his stellar career, but at the time he experienced temporary paralysis. For his part in the altercation, Green was suspended 13 days. This suspension did not really matter as his injuries and recovery forced him to sit out the remainder of the season and playoffs – where fittingly the Bruins would sweep the Blues after Bobby Orr’s infamous goal in overtime of game four in 1970. Even though Green was not technically part of the team the Bruins still gave him an equal share of their Cup bonus, and had his name engraved on the Cup. Green would return the following season and win the Cup with Bruins while actually being on the ice in 1972.

Maki was suspended 30 days, but the Blues would send him down to the AHL’s Buffalo Bisons, where he would spend the remainder of the season. Both Maki and Green were charged with assault by the Crown as well, but in separate trials both cases were acquitted.

So, remember that although the Cup Finals are a war right now, remember that in the 1960s, even preseason games were life-and-death, stick-swinging battles. Where laying your body on the line meant a great deal more than it does today.

Photo: Jeff Roberson/Associated Press